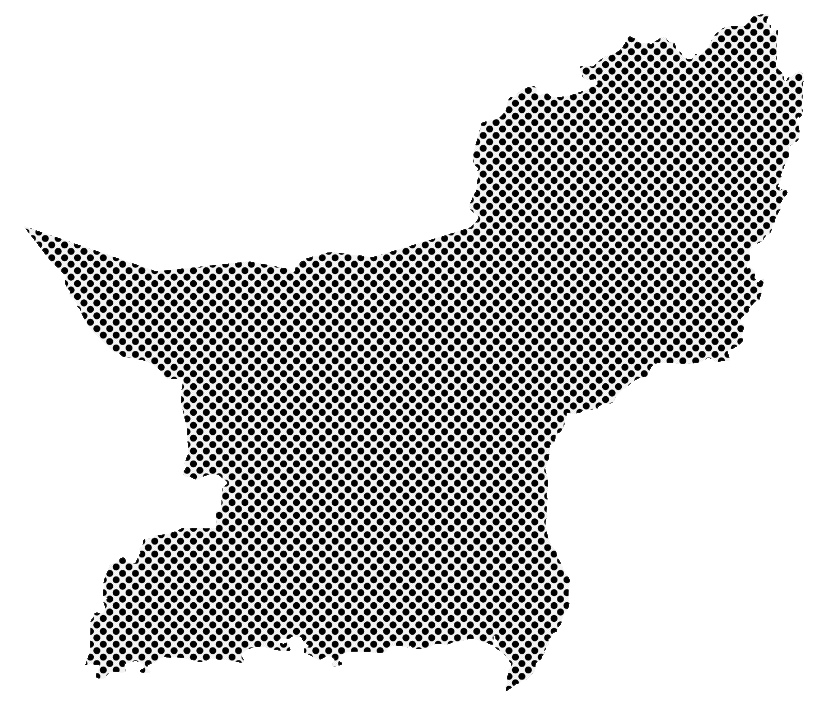

Balochistan

Living with Nothing

A series of security operations have punctuated Balochistan’s amalgamation as Pakistan’s fourth province — with the first in 1948, then across the 1960s and 1970s, and the last in 2002, to suppress insurgencies against state control of territory and resources. Bar the occasional lull over the years, such troubles have resurfaced without fail, triggering a harsh response from the state to crush insurgencies and activism. Consequently, the province’s relationship with the centre is a complicated one, marked by a deep sense of disaffection flowing from the state’s cavalier attitude to its grievances and concerns over the years.

“If anything illustrates and puts into sharp relief Balochistan’s deprivations, both historical and current, it is the state of its prisons.”

Detention Through Colonial and Post-Colonial Times

Two areas of concern around imperial expenditure in Balochistan stand out: the transformation of the province into a territory for expanding British military presence to control the borders with Afghanistan and Iran; and the maintenance of ‘law and order’ under the British as the new self-proclaimed rulers of various tribal groups.

- Under the British Crown Rule

- The Present

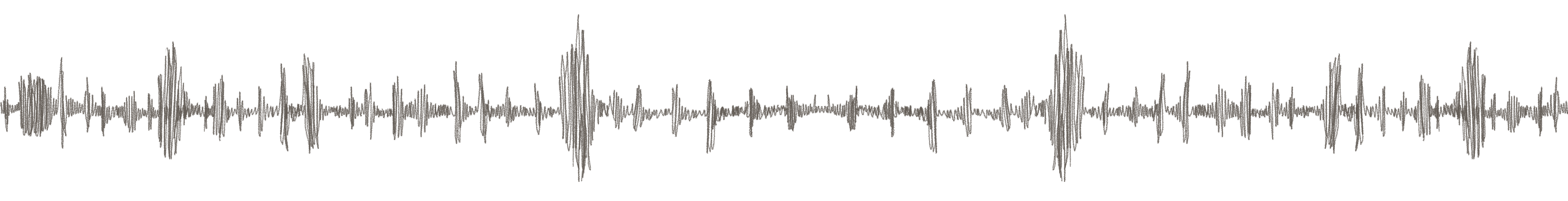

Author’s Voice-Notes

Stories of Incarceration

Into the Void

Courting Crime Out of Desperation

A Student Activist Disappears

Balochistan Statistics 2023

Prison Population Trend

as of Nov 2023 statistics

of it’s authorized capacity

Under Trial Prisoners

of all the prisoners are

under trial in only Balochistan

Prison Population in Balochistan

population in pakistan